By M. P. Regmi PhD, D. M. Basnet PhD, M. C. Perelstein, R. B. Ingram, & A. Sochos PhD

“Anyone can become angry – that is easy.

But to be angry with the right person to the right degree at the right time for the right purpose and in the right way – that is not easy.”

~ Aristotle

Abstract

Anger is a strong human emotion that can often become dysfunctional leading to aggression and conflict in human relationships. The aim of the present paper is to evaluate the effectiveness of an intervention developed by Van Leuven and colleagues using an anger scale developed by the same author. This will be initiated with a literature review concerning anger and anger cognition, followed by the results of the Life Without Anger (LWA) educational curriculum presented to 7th grade students throughout various schools in Nepal. It is believed by the authors that targeted education regarding anger cognition will have a positive outcome on students who participate in the curriculum.

Literature Review

Anger has five main mental afflictions which are wrath, resentment, spite, envy, and cruelty. Both western psychology and eastern philosophical traditions have identified anger as a potentially destructive emotion. Anger is a mental affliction states Goleman (1998), while extreme anger, or rage, can be defined as the “inability to process emotions emerging in life”. According to others, anger is a repugnant temporary insanity (Kemp & Strongman, 1995), a negative response associated with high heart rate and blood pressure, expressed through body language and behavior. Robert and Kay (2017) argue that anger sabotages happiness and leaves misery in its wake. A state of persistent anger is central in the so-called Type A Personality, coexisting with competitiveness, speed, and job over-involvement, a pattern associated with cancer and cardiovascular disease (Spielberger & Sarason, 1996).

The concept of Neuroticism refers to individual differences in the tendency to experience chronic negative emotions. Individuals diagnosed with neuroticism can often become angry, depressed, embarrassed, anxious, emotional, and insecure (Barrick, & Mount, 1991, McCrae, & John, O.P. (1992). Ekman (2004) describes increased perspiration when anger is intense. This is caused by the hypothalamus being closely engaged in our motives and emotions. Such actions and emotions as eating, drinking, pleasure, anger, and fear are all involved. Additionally, the thalamus is also involved in aggression, along with the amygdala which seems to activate the emotions of fear, rage, and frustration while damage to the amygdala typically results in a complete absence of anger and rage (Lahey, 1998). On the other hand, social constructionists are focusing on how anger and aggression are constructed interpersonally and socially (Gergen, 1991, 1999; Weishaar, 1993).

Freud linked anger with anxiety and guilt, while contemporary theories understand stress as a process that includes anger and anxiety, specifically defining them as the most frequent emotional reactions to stress. Spielberger (1995) indicates the effectiveness of stress management programs is often assessed by participants completing anxiety and anger measures at every session. According to some authors anger management should teach us how to forgive people (Regmi, Basnet, Aryal, 2021), while Perl (1995) used a particular type of Gestalt therapy called “Boom – Boom therapy”, an intense cathartic psychological treatment to release individuals from self-consuming anger. Boswell (1982) developed interventions attempting to address anger in children and his central aim was to help children understand anger.

In addition to western psychology, eastern philosophies are also rich resources for understanding human anger and its impact on peaceful life. In Tibetan Buddhism, there are three poisons: anger, craving, and delusion. Anger occurs in conjunction with sadness. According to Buddhist teachings, we must change our behavior through transformation and progress toward good behavior. Destructive emotions bring unhappiness to self and others. We try to refine our behavior and rejoice in other people’s qualities. We must cultivate humility and regard others’ good behaviors. Anger, craving, and delusion are three poisons.

Lord Krishna emphasized Samadhi in which one can attain perfect peace only in complete Krishna consciousness. He meditates on the transcendental self, or the supreme personality of God, known as Krishna consciousness. People meditate on peace and tranquility. Thus, a person can liberate his/her anger (Krodh, in Nepal and India). Saibaba, perfect yogi, had full control of wisdom like Buddha, Lao-tzu, Atri, Jesus, and had a perfect personality (Regmi, 1997). The Yogi conquers the organs, has full control over his anger due to wisdom, and attains tranquility. Uprooting anger offers hope and helps to forgive some, have a clear conscience, and replace anger with love.

A Krishna-conscious person meditates on the transcendental self (Text 19.20-23, p.291). The religious book of famous Buddhist text, ‘Dhammpad’ is as holy book which teaches how to eliminate anger. It is a collection of sayings of the Buddha in verse form and one of the most widely read and best-known Buddhist scriptures. The ‘Dhammpad’ (2013), as an indicator of true religious path, describes the holy man, Arhatas blessed and enlightened with no attachments, “A noble Arhat (sage) is harmless towards all living things”. Sandweiss (1975) stated that Sai Baba was impressed by the ascetic personality of Buddha, who was born in Lumbini in Nepal. Buddha was a spiritual saint and offered his emancipated philosophy of nirvana.

The mediators “spiritual path” is to traverse fear, anger, sadness, depression, joy, and love to arrive at serenity or silence. Zen teachings offer a useful means in the prevention of emotional disturbance such as depression and help to maintain the emotional health of professionals (Kwee, 1990). Men (Yan) and women (Yin) are reunited with their masculine and feminine, and in this way, they can reach individualization, and the self is enlightened, linked, and balanced. Taoist masters worked on a myriad of techniques, e.g., assimilation of lunar power, inspiration of light, solar energy, relaxation, and concentration, to reinforce vital energy (Chia, 1983). The work of Tu (1985) is especially important in assisting with the confusion of thoughts for creative transformation. Filial Piety is unique to Chinese people (Yong, & Hwang, Eds.).

Contemporary psychological work on anger in Nepal has been influenced by both the western and eastern intellectual traditions. Regmi & Basnet (2009) found that male employees scored higher anger cognition than their female counterparts, while Regmi& Basnet (2010) revealed that low control over the anger among Nepali bank employees created unmanaged circumstances in the workplace. A study by Regmi, Shakya, & Basnet (2012), found that female respondents have lesser anger cognition than male counterparts while there were significant differences in anger cognition and anger score in Nepalese adolescents between distinct cultural groups in anger score (Brahmin, Chhetri, Janajati, and Dalit; Regmi, Shakya, & Basnet, 2012). Gender differences were found among the Chhetri caste of Nepalese adolescents (Regmi et al., 2012).

In Nepal significant efforts have been made to build interventions towards developing emotional literacy among school-aged children and adolescents. Regmi, Basnet, & Tripathi (2010) emphasized that such interventions aim to transform anger into an acceptable positive emotion. Van Leuven (2010) argues that individuals are the center for the reasoning and final decision to act and that we learn to forgive and rid yourself of fear and anger through rehearsing anger-free behavior.

LWA 7th Grade “Life Without Anger” Curriculum Study Results

This study is based on the work by World Without Anger, an NGO in Nepal, run by Basnet, who have been offering their Life Without Anger Emotional Education Program to 7th and 8th graders in and around Kathmandu, since 2004. For this study, initially there were 693 paired Pre- and Post-Assessments collected from seventh (7th) grade students who participated in the Life Without Anger curriculum. All assessments were converted to digital format for analysis. Of the 693 paired assessments, 33 (4.76%) were found to have incomplete or errored data entries in either the student’s Pre- or Post-Assessment. This rendered those records to be non-compatible for a paired analysis and were removed. This left 660 student paired assessments to evaluate.

The Life Without Anger (LWA) anger test (Figures 1 & 2), authored by Van Leuven, is a 25-item assessment that asked the student to rate their level of anger on a 6-point Likert Scale from 0: Not at all angry, 1: A little angry, 2: Moderately angry, 3: Quite angry, 4: Greatly angry, 5: Cannot contain your anger, when faced with different life situations. The Pre- and Post-Assessments were identical when administered. The questions were designed to help the student understand how they respond in anger to stressful situations. They were asked to answer the twenty-five questions by circling one of the six responses that most clearly reflected how they believe they would personally respond in anger to each situation. The maximum anger score is 125. If the student reported having absolutely no anger, the score is zero. In general, the lower the total score, the greater the quality of life is assumed. The higher the score, the more difficult one’s emotional life is assumed.

Figure 1: Assessment Questions (part 1)

Figure 2: Assessment Questions (part 2)

The following table shows the overall results for the Pre-Assessment; the Post- Assessment; and the Delta (Pre-Assessment Scores minus the Post Assessment Scores)

| PRE-ASSESSMENT Total Score | POST- ASSESSMENT Total Score | TOTAL DELTA ∆ – PRE- to POST- ASSESSMENT TOTAL SCORES | |

| n= | 660 | 660 | 660 |

| MEDIAN | 54 | 43 | 9 |

| MEAN | 55.45 | 43.80 | 11.65 |

| MODE | 41 | 37 | 6 |

| MINIMUM | 4 | 0 | (62) |

| MAXIMUM | 125 | 113 | 79 |

| Standard Deviation | 18.62 | 17.52 | 22.16 |

Table 1: Pre- & Post-Assessment Comparison

Further examination of the Delta Scores revealed while in general the overall result was a decline in the level of anger reported by the students, there is an anomaly in the data. When examining the Pre-Assessment Scores to the Post-Assessment Scores it became apparent that the decrease in the level of anger was not across the entire spectrum of the student sample. 28.8% of the students had Post-Assessment Scores higher than the Pre-Assessment Scores. Table 2 below will demonstrate the anomaly.

| ETHNIC GROUPS | Percentage (%) | PRE > POST | PRE = POST | PRE < POST |

| TOTAL (n=660) | 100.0% | 69.5% | 1.7% | 28.8% |

| BRAMIN (n=80) | 12.1% | 6.8% | 0.3% | 5.0% |

| CHHERTI (n=162) | 24.5% | 17.9% | 0.5% | 6.2% |

| JANAJATI (n=308) | 46.7% | 33.8% | 0.8% | 12.1% |

| DALIT (n=67) | 10.2% | 6.5% | 0.2% | 3.5% |

| MEDEHI (n=43) | 6.5% | 4.5% | 0.0% | 2.0% |

Table 2: Pre- to Post– Score Comparison, by Ethnic Group

The Pre- vs. Post- Assessments Results (Table 3) show that 190 (28.8%) of the students with a range of difference of 61 with the lowest difference being 1 and 62 being the highest number difference for the Group PRE < POST. For the Group PRE > POST the range of difference was a negative range of 78 points represented by -1 being the smallest difference and –79 being the largest difference.

| Results | PRE > POST | PRE = POST | PRE < POST | ||

| MAX | (1.00) | 0 | 62 | ||

| MIN | (79.00) | 0 | 1 | ||

| n= | 459 | 11 | 190 | ||

| AVERAGE | (22.28) | 0.00 | 13.36 | ||

| Standard Deviation |

|

0.00 | 10.40 |

Table 3: Pre- vs. Post-Assessment Results

Charts 1 and 2 below look at the Delta averages by Ethnic and Gender Grouping as well.

Chart 1: Assessment Averages & Delta Averages

Chart 2: Assessment Averages, by Ethnic group and Gender

The following tables will provide an overview of each Ethnic Group Response.

‘>0’ represents the Pre-test score being greater than the Post test score; ‘0’ represents the Pre- and Post- scores being equal; and ‘<0’ represents the Post-test scores being higher than the Pre-test scores.)

| BRAMIN | ||||

| >0 | 0 | <0 | TOTAL | |

| MALE | 22 | 2 | 12 | 36 |

| % | 27.5% | 2.5% | 15.0% | 45% |

| FEMALE | 28 | 0 | 16 | 44 |

| % | 35.0% | 0.0% | 20.0% | 55% |

| TOTAL | 50.0 | 2.0 | 28.0 | 80 |

| % | 62.5% | 2.5% | 35.0% | 100% |

| OVERALL % | 7.6% | 0.3% | 4.2% | 12.1% |

| 660 | 80 | |||

Table 4: Ethnic group – BRAMIN

| CHHERTI | ||||

| >0 | 0 | <0 | TOTAL | |

| MALE | 57 | 2 | 27 | 86 |

| % | 35.2% | 1.2% | 16.7% | 53% |

| FEMALE | 61 | 1 | 14 | 76 |

| % | 37.7% | 0.6% | 8.6% | 47% |

| TOTAL | 118 | 3 | 41 | 162 |

| % | 72.8% | 1.9% | 25.3% | 100% |

| OVERALL % | 17.9% | 0.5% | 6.2% | 24.5% |

| 660 | 162 | |||

Table 5: Ethnic group – CHHERTI

| ANAJATI | ||||

| >0 | 0 | <0 | TOTAL | |

| MALE | 89 | 1 | 31 | 121 |

| % | 28.9% | 0.3% | 10.1% | 39% |

| FEMALE | 150 | 2 | 35 | 187 |

| % | 48.7% | 0.6% | 11.4% | 61% |

| TOTAL | 239 | 3 | 66 | 308 |

| % | 77.6% | 1.0% | 21.4% | 100% |

| OVERALL % | 36.2% | 0.5% | 10.0% | 46.7% |

| 660 | 308 | |||

Table 6: Ethnic group – JANAJATI

| DALIT | ||||

| >0 | 0 | <0 | TOTAL | |

| MALE | 19 | 0 | 10 | 29 |

| % | 28.8% | 0.0% | 15.2% | 43.9% |

| FEMALE | 24 | 0 | 13 | 37 |

| % | 36.4% | 0.0% | 19.7% | 56.1% |

| TOTAL | 43 | 0 | 23 | 66 |

| % | 65.2% | 0.0% | 34.8% | 100% |

| OVERALL % | 6.5% | 0.0% | 3.5% | 10.0% |

| 660 | 66 | |||

Table 7: Ethnic group – DALIT

| MEDEHI | ||||

| >0 | 0 | <0 | TOTAL | |

| MALE | 17 | 0 | 10 | 27 |

| % | 39.5% | 0.0% | 23.3% | 62.8% |

| FEMALE | 13 | 0 | 3 | 16 |

| % | 30.2% | 0.0% | 7.0% | 37.2% |

| TOTAL | 30 | 0 | 13 | 43 |

| % | 69.8% | 0.0% | 30.2% | 100% |

| OVERALL % | 4.5% | 0.0% | 2.0% | 6.5% |

| 660 | 43 | |||

Table 8: Ethnic group – MEDEHI

As can be seen by the tables it is evident that most of the students (~70%) decreased their Anger Level scores across the Ethnic Groups. In general, Females decreased their scores more than Males. Table 9 will demonstrate this.

| Results | BY GENDER | ||

| >0 | 0 | <0 | |

| MALE (n=299) | 200 | 5 | 94 |

| % | 30.30% | 0.76% | 14.24% |

| FEMALE (n=361) | 259 | 6 | 96 |

| % | 39.24% | 0.91% | 14.55% |

| TOTAL (n=660) | 459 | 11 | 190 |

| % | 69.55% | 1.67% | 28.79% |

Table 9: Male & Female Response Categories, by Gender

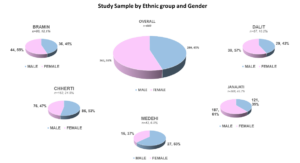

The following is the demographic breakdown of the students:

Figure 3: Sample Study, by Ethnic group and Gender

Summary

In summary, the data indicates that the LWA curriculum positively influenced the level of anger of the 7th grade students. A small percentage showed no difference (1.67%) between Pre and Post Assessment scores, and some showed a higher Post Assessment Score over their Pre-Assessment Score (28.79%). Further research is warranted as there are a number of reasons potentially contributing to such occurrences.

Both the literature review and the LWA 7th grade study indicate that the lessening of the level of anger is possible through a combination of education about what anger is and what occurs behaviorally when acting out of anger. This indicates that there is significant and meaningful potential for reducing the level of anger cognition through an educational curriculum that addresses the full spectrum of the Cognitive Domain (Thinking); Affective Domain (Feeling); and Behavioral Domain (Actions). Such a curriculum addresses the knowledge, skills, and attributes necessary to make better decisions regarding situations when an individual’s level of anger is increased or increasing. This presents an opportunity for further examination of the efficacy of the LWA Educational Curriculum for the Nepalese Educational System.

Dhammpada Buddhist text has an entire chapter on anger (chapter 17), and instructs, “Through kindness, one should overcome anger, through goodness one should overcome a lack of goodness…” (page 222).

References

- Barrick, M. R., & Mount, M. K. (1991). The Big Five personality dimensions and job performance: A meta-analysis. Personnel Psychology, 44 (1), pp. 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1991.tb00688.x

- Bhagavad-Gita As it is, second Edition (1986). By A.C. Bhaktivedant Swami Prabhupada. Harekrishna Land Juhu Mumbai 400 049, India.

- Boswell, J. (1982). Helping Children with their Anger. Elementary School Guidance and counseling, pp.23-29.

- Goleman, D. (1998). Working with Emotional Intelligence, New York: Bantam Book. https://doi.org/10.1002/ltl.40619981008

- Hall, S.P. (2009). Anger, rage and relationship: An empathic approach to anger management. London: Rutledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203871911

- Horschild, A.R. (1983) The managed heart: Commercialization of human feeling. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Kemp, S., & Strongman, K.T. (1995). Anger theory and management: A historical analysis. The American Journal of Psychology, 108(3). pp. 397-417.https://doi.org/10.2307/1422897

- Kushner, H.S. (1981). When bad things happen to good people. Shocken books. pp. 122-124

- Leuven, D.V. (2007). SEWA Life Without Anger – Student Manual, Sunlight Publication Kathmandu, Nepal.

- McCrae, R. R., & John, O. P. (1992). An introduction to the five-factor model and its applications. Journal of Personality, 60 (2), 175–215. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1992.tb00970.x

- Regmi, M. P., Basnet, D. M., & Aryal, N.P. (2021). Management of Anger in the Context of Constructionism and Contributions of Derrida, Lacan, Hattie, Spielberger, Mishra, and Sochos. International Journal of Learning and Development, 11(4), 1. doi:10.5296/ijld. v11i4.19138

- Regmi, M.P. (2018). Aspects of Anger Cognition and its management, WWA International Journal, Vol.7, No.1, ISSN 2091-0398

- Regmi, M.P., & Basnet, D.M. (2009). Emotional awareness and anger cognition among Nepalese adolescents and adults of corporate sector. WWA International Journal, Vol.1, No.1, pp.2-12

- Regmi, M.P., Basnet, D.M., & Tripathi, M. (2010). Leadership model and anger control: A Nepalese study. WWA International Journal, Vol. 2, No.1, pp.1-2

- Regmi, M.P., Shakya, S., & Basnet, D.M. (2012). Anger cognition of Nepalese adolescents. WWA International Journal, Vol. 3&4, No.1, pp.1-4

- Sandweiss, Samuel, H. (1995). Sai BABA. The Holy Man and the Psychiatrist. M. Gulab Singh & Sons Ltd., New Delhi: India

- Spielberger, C.D. (1988). Professional manual for the state-trait anger expression inventory. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources. https://doi.org/10.1037/t29496-000

- Spielberger, C.D., & Sarason, I.G. (Eds.). (1996). Stress and emotion: Anxiety, anger and curiosity, Behavioral Sciences, (pp.1-16). New York: Taylor & Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203782385.

- Potegal, M., & Stemmler, G. (2010). International Handbook of Anger. Chapter 4, Constructing a Neurology of Anger. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-89676-2

- Tu, W.M. (1985). Confucian thought: Selfhood as creative transformation. New York: State University of New York Press.

- Yong, K.S., & K.K., Hwang (Eds.). Psychology and behavior of Chinese people: Proceedings of the first interdisciplinary Conference (pp.141-179). Taipei: National Taiwan University, Institute of Psychology.

- Leuven, D.V. (2007). Life Without Anger – Student Manual, Sunlight Publication, Kathmandu, Nepal.

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1QEuADfzSgTXlXvL7NUySO3Cfewv0y5q7CEL8HUIG1MA