Also available as a Google Doc: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1xFnZhyPNUgM2422RgGFOnMu3a3-S0Ttc

Authors:

Aliyah Arif Durrani, MA – Clinical Psychology, KC College, Mumbai, India.

Myron Doc Downing, PhD, USA

Abstract

The present paper is an overview of a theoretical orientation that analyzes the influence of affect, cognition, and behavior in human social interactions. Early researchers have extensively studied different parts of the tripartite paradigm—popular theories such as behaviorism, developed by B.F. Skinner focused on studying behavioral aspects using principles of conditioning, whereas the psychodynamic approach pioneered by Freud emphasized understanding unconscious mental processes.

More recently, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) has been considered for treating diverse mental health conditions such as anxiety, depression, bipolar disorders, and personality disorders. The therapy is based on identifying and manifesting alternative ways of challenging dysfunctional cognitions and their underlying influence on affective and behavioral functioning.

In the review of past literature, the study of the affect within such a paradigm has received little recognition. Thus, this paper aims to outline the role of affect in social cognition and behavior as our perceptual experiences influence our affective states, which thereby help shape behavioral tendencies for dysfunctional and optimal human functioning. In other words, the CABT perspective advocates a therapeutic methodology that incorporates all components of the tripartite paradigm as forms of effective change in order to achieve personal and global peace. Past relevant research studies will be used to illustrate a comprehensive understanding of the topic. Further recommendations for future research work will be included.

Keywords: Affect, Cognition, Behavior, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, Cognitive Affective Behavioral Therapy, Emotional Intelligence, Peace, Positive Mental Health

Introduction

The nature of discussions and techniques employed by clinicians emphasized the revolutionary change that had surfaced with new methodological principles of research work. The dynamic shift from a traditional philosophical approach to gaining an evidence-based perspective highlighted the analytical mindset that was prevalent among our contemporary theorists. In the early 1960s, the transition to the first wave of behavior therapy was introduced. It included principles of classical and operant conditioning based on methods of observing, reinforcing, and modifying behavior to produce desirable outcomes that resulted in an adaptive change (Skinner, 1953; Watson, 1925). Some of the techniques included key aspects of behavior modification, exposure-based therapies, and systematic desensitization.

Although popular at the time, Bandura’s social learning theory explains the advanced idea of imitation or modeling in our lives, particularly in young children and their ability to implement the behaviors of their role models, such as parents, as forms of habitual practice. Skinner’s theory of operant conditioning based on reinforcement contingencies, in which the associated consequences, i.e. rewards or punishments, predicted the likelihood of the behavior occurring in the future. The primary tenets of such behavioral principles were subjected to intense scrutiny by several theorists. According to contrary opinions, the advent of behavior therapy was limited in accounting for all facets of human behavior (Mahoney, 1974), including studying the mental processes that underlie one’s actions.

The limitations of first wave therapy advocated the emergence of another successive wave of behavior therapy known as cognitive-behavioral therapies, an umbrella term that incorporates theories like rational-emotive behavior therapy and cognitive therapy. The traditional CBT perspectives were shaped by assessing the function of underlying cognitive mechanisms while investigating overt behavioral responses. The second wave marked the beginning of a “cognitive revolution” that took place in the 1960s and 70s (Mahoney, 1977) which studied the unconscious mental representations of individuals and cognitive reappraisals of events. Some of the techniques employed included cognitive restructuring and relaxation training, in which clients learned how to recognise and alter the faulty thinking patterns that influenced their maladaptive behavioral responses. Such evidence-based methods yielded efficacious results by fostering healthy patterns of cognition and behavior (Mahoney, 1977).

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT), one of the most extensively researched methods of psychotherapy (Hofmann SG, Asnaani A, Vonk IJ et al., 2012), was deemed the “gold standard” technique in evidence-based literature (David, Lynn, & Ellis, 2010; Hofmann, Asnaani, Vonk, Sawyer, & Fang, 2012). Studies have proven its clinical efficacy using effective randomized-controlled designs (Meyer and Scott, 2008). Furthermore, the therapy was regarded as a viable form of treatment for diverse demographic segments, age groups, cultural backgrounds, etc, in treating psychiatric and medical conditions. (Dobson & Dobson, 2017; Hofmann, 2013).

The theory of CBT was disseminated on the principle that our cognitive appraisals could be monitored and brought under scrutiny. Examination and modification of cognitive thought processes was carried out in a systematic manner between the therapist and client as part of treatment, with a collaborative effort attributed to the reformation of such maladaptive appraisals into adaptive ones (Wright, 2006). However, critics of cognitive theory contended that transforming such irrational cognitions required a continuous effort of modification. As a result, there was a dynamic shift in the traditional therapeutic foundation, giving rise to a new movement known as the third wave.

The ‘third wave’, also known as the ‘third generation of CBT’ (Hayes SC,2004; 2006; Öst LG,2008), consolidated new integral elements with previous frameworks as forms of an eclectic model. The movement included adding multiple systems techniques with shared components such as acceptance, mindfulness, cognitive defusion, and other thought-changing tools and techniques. These tools gave rise to new therapeutic paradigms which became popular, including Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT; Hayes & Strosahl, 2004), Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT; Linehan, 2014), and Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT; Segal et al., 2012).

The objective of the new trend was to understand the contextual relationships of cognitions rather than their implicit content, which was the earlier focus of traditional CBT approaches (Hayes SC, Luoma JB, Bond FW, Masuda A, Lillis J, 2006). The emphasis on metacognitive processes was one of the key distinguishing features that elaborated our understanding based on the contextual concepts such as anxiety about anxiety, distress about depression, and thinking about thinking (Flavell, 1979). According to Herbert, Forman, and England (2009), the metacognitive strategies were founded on notions of acceptance of our dysfunctional cognitions and mindful-based awareness and skill of the process of change that occurred in relation to both thoughts and emotions (Hayes, 2004; Roemer & Orsillo, 2003). The new behavioral and cognitive therapies emphasized the goal of psychological flexibility by living a meaningful life consistent with one’s values (Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, Wilson KG.,1999).

In a descriptive analysis by Forman and Herbert (2009), it was suggested that behavioral theories influenced both traditional and modern CBT techniques. Although both therapies used similar behavioral principles in practice, there were discrepancies found between their theoretical orientations. Second-wave therapists focused on changing the content of irrational or dysfunctional cognitions with the goal of symptom relief. In contrast, third-wave therapists highlighted the role of metacognitive processes in the pursuit of holistic well-being and valued living. A cross-sectional study suggested that modern CBT therapies, such as ACT and DBT, had moderately significant effects on therapeutic-based outcomes, similar to traditional CBT therapies (Butler et al., 2006; Öst, 2008).

According to Hayes (2004), despite differences in the strategic techniques used by theorists across all CBT generations, the conceptualization of the three waves is attributed to more similarities in their concepts than differing backgrounds of opinions. Thus, there were overlapping differences that blurred the fine distinction between these treatment modalities. It was assumed that the new third wave should not be classified as a separate system but rather as an extension of the traditional CBT model, with which it shared therapeutic-based premises (Hofmann SG, Asmundson GJG, 2008). For instance, the DBT model was said to be an integration of traditional CBT techniques with additive elements of acceptance (Marsha Linehan, personal communication, August 28, 2007).

The dyadic interaction between the models provided a large body of literature for clinicians to employ an educative approach with appropriate solution-focused strategies (Dobson & Dobson, 2017). According to previous literature, studies had empirically tested different forms of techniques using various elements across CBT approaches that have proven to work effectively in addressing specific needs of target populations, such as adolescents and young adults suffering from generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia, post-traumatic stress disorder, and depression. (Wolitzky-Taylor KB, Arch JJ, Rosenfield D et al., 2012).

Such early therapeutic models primarily formulated their work around the three basic functional systems of mode, namely cognitive (a.k.a. information-processing), affective, and behavioral approaches. Each mode, by the nature of its attributes, plays a dynamic role within the integration of one’s personality structure and works harmoniously in attaining one’s external and internal demands. A prime example of the integrated network at operating functions would be a phobic reaction to an external stimulus resulting in the perception of a threat (cognitive), feelings of fear or anxiety (affective), and the use of safety net behaviors (Salkovskis, 1996), such as active avoidance of a situation (behavioral).

Cognitive processing, described as the pattern of thinking, includes the ability to reason, form judgments and opinions, solve problems, etc. Such processing typically occurs within the unconscious realms as automatic thoughts (Kihlstrom, 1990), whereas other cognitions penetrate human awareness as conscious thoughts.

Affective processing reflects our emotional functioning and capability of experiencing various primal emotions such as anger, sadness, joy, etc. that serve as important evolutionary survival mechanisms. Positive emotions create the essence of sensory pleasure by emitting dopamine neurotransmitters through our brain’s “rewarding” mechanisms. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) explains the concept of psychological flexibility by adhering to the acceptance of healthy negative emotions, such as sadness and anger, as sources of goal-directed change and personal growth for individuals (Hayes, Luoma, Bond, Masuda & Lillis, 2006). As a result, affective states (whether positive or negative) have served an adaptive function by shaping our social behavior and interactions (Beck et al., 1985).

Behavioral processing describes the ability to carry out both potent action tendencies such as fight-or-flight responses in the face of imminent threats as involuntary reflex actions (Beck et al., 1985) and voluntary controlled responses, such as riding a bicycle or walking.

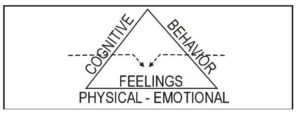

The three components, i.e., cognitive, affective, and behavioral, work as flexible intrinsic systems of units that regulate optimal human functioning. The integrated network has been well-established in various studies; for example, Greenberger and Padesky (1995) developed what was known as the “hot-cross bun model,” which illustrated how the basic system components complement each other in their function, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The ‘hot-cross bun model’ developed by Greenberger and Padesky (1995)

One of the core characteristics of CBT therapy was hypothesized to be the cognitive model (Beck, 1964). This model prescribed a fundamental learning principle in which dysfunctional negative thoughts can manifest as disturbed emotional and behavioral functioning. In other words, an individual’s perception of situational events can become distorted with the formation of negative schemas which influence one’s affective and behavioral state. As a result, it was determined that our perceptual beliefs had a significant impact on our feelings and behavior.

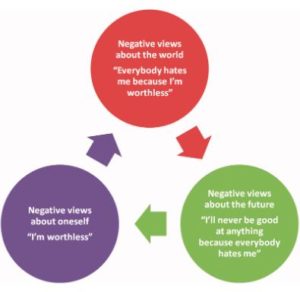

Schemas are mental cognitive frameworks that organize information and form ways of relating to the self, the world, and the future (Beck, 2013). According to research, it was suggested that depressed individuals formed perceptions that were negatively biased (Beck, 1976) and construed thoughts based on the cognitive triad. The cognitive triad, proposed by Aaron Beck, represented an individual’s belief system, which was characterized by negative evaluations of oneself, others, and the future (Hollen & Beck., 1979) (see Figure 2). Such perceptions operated as a mediational mechanism for change reflected in one’s bodily actions. Thus, CBT as a theoretical perspective primarily advocated for cognitive and behavioral change as a means of restoring equilibrium among the three paradigmatic elements. This was implicitly illustrated by examining and transforming maladaptive appraisals in an effort to establish realistic belief systems, the validity of which was measured by one’s behavioral outcome (Kendall & Bemis, 1983). Such case transformations benefited individuals in terms of relapse prevention and providing short-term symptom relief (Beck & Dozois, 2014; Driessen & Hollon, 2010).

Figure 2. The cognitive triad proposed by Aaron Beck (1976)

Figure 2. The cognitive triad proposed by Aaron Beck (1976)

However, in terms of producing a desirable form of change, the cognitive model accounted for less of the affective principle. Thus, as a result, the current paper proposes a therapeutic-based method for incorporating the role of affect within the cognitive-behavioral paradigm in an effort to identify one’s self-actualizing tendencies.

Cognitive-Affective-Behavioral Therapy (CABT)

Cognitive-Affective-Behavioral Therapy (CABT) was first proposed as a theoretical orientation in 1973. In tracing the origin of the theory, it was discovered that CABT and CBT perspectives shared therapeutic techniques that were principally guided by behavior and cognitive-based approaches. However, the two theories had distinct ideologies with opposing underlying principles.

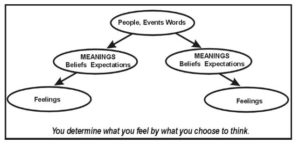

CBT practitioners, when dealing with problems primarily focused on client change, generally embody the notion of cognitive and behavioral constructs wherein dysfunctional thoughts are examined and modified as rational cognitions, which thereby influence social behavior. On the other hand, the CABT perspective incorporates the tripartite paradigm of cognitive, affective, and behavioral states as sources of effective change. The model is deeply embedded in the presupposition of adhering to a sequential order of events, i.e. Cognitive ->Affective -> Behavioral (see Figure 3 below).

Figure 3. The sequential order of events established within the CABT model

In the CABT model, the activating events are interpreted by our perceptual beliefs through the concept of language, which aids in word meaning and inference-based processes. The meaning attributed to the thought further determines the current state of feelings experienced by the individual, which thereby dictates one’s behavioral choice of actions (see Figure 4 below). The intrinsic unit of therapeutic-based alliances is the sound resonance of all three components as causes of optimal human functioning, with the success rate of therapeutic outcomes measured as implications of one’s long-term behavioral goals (Orlinsky et al., 2004).

Figure 4. The CABT Model

Our perception of people, events, and words generate several different interpretations or expectations, leading us to inconclusive results or heedless moments on how to feel and act in such particular situations. For example, someone bumps into you while you are running down the school hallway. You might immediately think this person is so rude and angrily respond, “Watch where you’re going,” while the other person turns around, his face feeling extremely apologetic, and says, “You seem to be in a bit of a hurry. Sorry for keeping you behind.” His statement stuns you and leaves you perplexed as to how to respond. You consider the situation and decide whether to remain angry at the person and continue on your way to class, or to linger behind for a moment and apologize to him, accepting the situation as a result of your tardiness. Thus, our initial judgment is shaped by the meaning that we attribute, which defines our state of feeling and thereby enables us to act in particular ways.

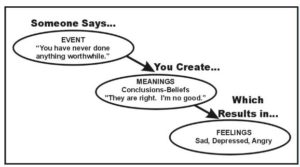

Let us consider another example, depicting how our sense of autonomy allows us to choose our thoughts patterns, which then determine how we feel and how our behavioral actions are influenced by these feelings, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5. An illustration of an example concerning what we choose to think and its impact on our feelings and behavior.

Dr. Albert Ellis, a psychotherapist, introduced the ABC model (see Figure 6 below) as a framework for correcting irrational assumptions with alternative rational beliefs in order to modulate our emotional and behavioral reactions. He believed that the activating event was reinforced by our belief systems, which further perpetuated positive or negative emotional and behavioral consequences (Oltean et al., 2017). In other words, Ellis considered it a fundamental principle that an individual’s belief system was the antecedent cause of one’s feelings as well as their actions.

Figure 6. The ABC Model

Rational and irrational cognitions, also known as hot cognitions (Abelson and Rosenberg, 1958) or evaluative cognitions of situation appraisals (David et al., 2005b), function as a conscious intermediary between the event and reciprocal mechanisms. This demonstrates a sense of autonomy in the process of assigning meaning to such cognitions and thus being able to respond to situations appropriately. For instance, in the preceding example, you may have accepted the hallway incident as a result of your negligence and confronted the person by taking responsibility for your unreasonable and crude behavior. The ability to make such deliberate decisions, however, may not always be recognised by the individual, as such evaluations are profoundly shaped by deep-seated schemas or core beliefs that subconsciously construe one’s sense of reality (David et al., 2005b). Therefore, we construct meaning from our surroundings and the actions of others using evaluative cognition, either consciously or unconsciously.

Meaning-making is a process, albeit a byproduct of human social cognition. The complex use of skills and language has sparked our evolutionary history as the highest species of homo sapiens among other life forms on Earth. Language as a tool allows us to communicate and engage in intimate social interactions. However, such social skills are inherited as a double-edged sword. On the one hand, language can be used in problematic ways, limiting our ability to express our inner selves and desires. For example, it may appear difficult to explain the process of riding a bicycle by using words alone, and we may be forced to rely on our procedural memory instead. Another example using a classic metaphor that explains the concept of ‘language trap’ is that even if you tell yourself not to think about the pink elephant in the room, you will probably find yourself doing just that. Thus, language may be composed of words, which are phonological structures of syllables with definitions, but we assign meanings to words.

“Men are not disturbed by things, but by the view they take of them.”

Epictetus 55–135 AD

Language provides us with a sense of control over its use of fluency. According to Maslow’s hierarchy, one of our basic psychological needs is to gain acceptance and a sense of belonging through the eloquent use of words by describing abstract traits such as love, kindness, justice, peace, etc. (Maslow, 1943; Barrett et al. 2007). Another technique that is widely used in ACT theory is cognitive defusion, the ability to evaluate our thoughts as mere external events through the use of language. For example, we use the standard ACT phrase “I am having the thought that…” as an additive element to each of our negative thoughts. Thus, “I am sad” can be translated as “I am having the thought that I am sad.” The technique enables us to “defuse” or externalize such thoughts from governing our “self” and take into account the necessity of acting upon them.

Research findings suggest that acceptance shown towards one’s emotions and thoughts that are judged as ‘unacceptable’ or ‘deviant’ helps the individual to diffuse such mental experiences from causing interference in one’s daily life (Campbell-Sills, Barlow, Brown, & Hofmann, 2006; Singer & Dobson, 2007) by engaging in less ruminative thinking (Mennin & Fresco, 2013) and in adverse meta-emotional reactions such as feeling ashamed about having anxiety or feeling guilty about being sad (Mitmansgruber, Beck, Höfer, & Schüßler, 2009). As a result, changing our relationship with our thoughts alters the process of determining how we feel, as shown below in Figures 7 & 8. A quote by David Burns, the famous author of Feeling Good, stated, “You feel the way you do right now because of the thoughts you are thinking at this moment.” Thus, the meaning we connote to our words, in turn, creates our feelings.

“Feelings are not good or bad, but thinking makes them so.”

William Shakespeare

Figure 7. Our feelings about other people, events, or words are mediated by our belief system.

Figure 8. An example illustrating how our perception of an event influences our feelings.

According to a preliminary analysis of previous therapeutic approaches, theorists consolidated by using the three component modes, namely cognition, affect, and behavior, either in one or a set of combinations within their therapeutic frameworks. For example, early psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud focused much of his work on analyzing the content of unconscious thoughts, which he believed were manifested by one’s past experiences, and thus his theory permeated a cognitive-based approach. Other prominent thinkers included B.F. Skinner, a renowned behaviorist, advocated the sole use of behavior modification techniques to address therapeutic problems. Humanistic psychologist Carl Rogers attributed proper recognition to one’s state of feelings and responded to the imperative need for training therapists to use the unconditional acceptance model during client-therapist interactions. Fritz Perls, the founder of Gestalt therapy, instilled the belief in using a combination of cognitions and feelings, whereas Albert Ellis implemented a cognitive-behavioral therapeutic approach (see Figure 9 below). While early therapeutic work largely undermined the use of all three modes of elements, CABT regarded the incorporation of an integrational network to be its theoretical foundation.

Figure 9. Early theorists and their therapeutic approaches

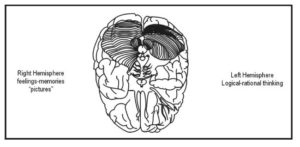

Another characteristic aspect in which the CABT perspective differed from the CBT model was its basis in neural mechanisms. Although CBT was associated with the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex region and was relatively dominant in left-brain thinking (Siegle et al., 2011), there were alternative methods of intervention that increasingly valued right-hand processing approaches with successful therapeutic-based outcomes (Norcross & Wampold, 2011; Magnavita, 2006). Such approaches included investigating skills such as creativity, flexibility, regulation of emotional arousal, and interpersonal abilities (Grabner, Fink, & Neubauer, 2007; MacNeilage, Rogers, & Vallortigara, 2009), reflecting the high emotional tendencies of “clinical intuition” prevalent among expert opinions (Bolte & Goschke, 2005).

However, clinicians who use a black-and-white thinking approach in their endeavors, employing techniques of either analytical reasoning (cognitive approach) or flexible reasoning (affective approach), may set high standards of a ceiling effect on therapeutic-based progress by risking the formation of a sound client-therapist alliance (Ackerman & Hilsenroth, 2001). Thus, CABT does not limit itself to a single viewpoint but rather encourages the integration of left-brain and right-brain approaches in client care. The theoretical perspective includes cognitive (left) and affective (right) brain systems that work in tandem by addressing problems with solution-specific techniques based primarily in each domain.

The left cognitive sphere encompasses both logical concepts and rational beliefs, as well as irrational, contradictory belief systems that coexist independently. Some examples of firmly held beliefs that coincide with their mutual counterparts include, “If at first, you don’t succeed, try again, try again.” Vs “If you can’t do a job right the first time, don’t do it at all.” ; “Distance Makes The Heart Grow Fonder” Vs “Out of sight, Out of mind”. The right affective side of the brain, on the other hand, responds to visual images and stores information based on what it “sees.” As a result, the display of the pictorial image triggers the body to react in the “here and now”. For example, when a childhood traumatic incident or image suddenly emerges in your mind and is retrieved by the affective brain system, your body begins to react with symptoms of intense anxiety, fear, and numbness. Due to the visual mental image that has triggered your bodily actions, you are said to be experiencing a vivid “flashback,” a prominent symptom of post-traumatic stress disorder, also known as PTSD. Thus, CABT denotes a dualistic model of thinking using both left and right approaches, wherein the former is primarily focused on thoughts or cognitions and the latter is based on visual mental images (see Figure 10 below).

Figure 10. The approaches used by right and left brain hemispheres

A therapist with good clinical judgment may use either of the two strategic approaches based on the client’s presenting problem to restore the equilibrium medium between the two operating systems, i.e., affective and logical. Let us consider a hypothetical example to demonstrate the importance of the two brain approaches working in tandem. If, on the one hand, your logical self believes that you determine your own sense of self-worth and not from the opinion of others, and on the other hand, your emotional self keeps reiterating the image of your father sitting on the bench, watching you play, and you find yourself become anxious about scoring a goal to impress him—which has often been difficult because he has always reprimanded you for being a failure. You may believe your logical self is telling a fallible lie that appears to contradict your reality, but find yourself aligned with your mental image as if it were true. Thus, a therapist will focus on using techniques such as visualization or role-playing that may aid in rewiring our feelings associated with such intrusive images in accordance with our logical beliefs. Such re-alignment facilitates the process of one’s long-term behavioral change.

Brain-integrative approaches have demonstrated better client-centric outcomes (Schore, 2012), with tenable solutions as problem-solving strategies. Such outcomes can be outlined using right-handed brain processing to find potentially viable solutions and left-handed brain processing to select the best solution-fit approaches (Cozolino, 2010). According to the first proponent of attachment theory, “clearly the best therapy is done by the therapist who is naturally intuitive and also guided by the appropriate theory” (John Bowlby, 1991).

Thus, CABT as a theoretical orientation proposes two important tenets: First, what you choose to think determines what you feel, and you choose your behaviors from what you feel. Second, when dealing with real-world scenarios, the theory employs two-way strategic thinking, namely the affective and logical brain approaches. Thus, seeking potential solutions requires establishing an integrative model as an effective conflict resolution strategy. Future research studies are thereby suggested to further explore the different regulation strategies that are used by the left-brain and right- brain approaches and their effects on therapeutic-based outcomes. Furthermore, the role of affect as a catalyst for effective change must be investigated.

REFERENCES

Brown, L. A., Gaudiano, B. A., & Miller, I. W. (2011). Investigating the similarities and differences between practitioners of second- and third-wave cognitive-behavioral therapies. Behavior modification, 35(2), 187–200. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145445510393730

Cherry, K. (2022, August 14). Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Verywell Mind. https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-maslows-hierarchy-of-needs-4136760

David, Daniel & Hofmann, Stefan. (2013). Another error of Descartes? Implications for the “third wave” Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy. Journal of Cognitive and Behavioral Psychotherapies. 13. 115-124.

Dozois, David J. A., “Historical and philosophical bases of the cognitive-behavioral therapies” (2019). Faculty Publications. 9. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/huronpsychologypub/9

Duncan, S., & Barrett, L. F. (2007). Affect is a form of cognition: A neurobiological analysis. Cognition & emotion, 21(6), 1184–1211. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930701437931

Fenn K, Byrne M. The key principles of cognitive behavioural therapy. InnovAiT. 2013;6(9):579-585. doi:10.1177/1755738012471029

Field, Thomas. (2014). Integrating Left-Brain and Right-Brain: The Neuroscience of Effective Counseling. The Professional Counselor. 4. 19-27. 10.15241/taf.4.1.19.

Ford, B. Q., Lam, P., John, O. P., & Mauss, I. B. (2018). The psychological health benefits of accepting negative emotions and thoughts: Laboratory, diary, and longitudinal evidence. Journal of personality and social psychology, 115(6), 1075–1092. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000157

Forgas, Joseph. (2002). Feeling and Doing: Affective Influences on Interpersonal Behavior. 13. 1-28. 10.1207/S15327965PLI1301_01.

Gloster, Andrew & Walder, Noemi & Levin, Michael & Twohig, Michael & Karekla, Maria. (2020). The empirical status of acceptance and commitment therapy: A review of meta-analyses. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science. 18. 181-192. 10.1016/j.jcbs.2020.09.009.

Hayes, S. C., & Hofmann, S. G. (2021). “Third-wave” cognitive and behavioral therapies and the emergence of a process-based approach to intervention in psychiatry. World psychiatry : official journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 20(3), 363–375. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20884

Hayes, S. C., & Hofmann, S. G. (2017). The third wave of cognitive behavioral therapy and the rise of process-based care. World psychiatry : official journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 16(3), 245–246. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20442

Hofmann, S. G., Sawyer, A. T., & Fang, A. (2010). The empirical status of the “new wave” of cognitive behavioral therapy. The Psychiatric clinics of North America, 33(3), 701–710. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2010.04.006

Izard C. E. (2009). Emotion theory and research: highlights, unanswered questions, and emerging issues. Annual review of psychology, 60, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163539

McLeod, S. (2019). [cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)]. What is CBT? | Making Sense of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy – Simply Psychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/cognitive-therapy.html

Oliver, Joseph & O’Connor, Jennifer & Jose, Paul & Mclachlan, Kennedy & Peters, Emmanuelle. (2012). The impact of negative schemas, mood and psychological flexibility on delusional ideation – mediating and moderating effects. Psychosis. 4. 6-18. 10.1080/17522439.2011.637117.

Selva, J. (2018, March 8). What is Albert Ellis’ ABC model in CBT theory? . PositivePsychology.com. Retrieved October 31, 2022, from https://positivepsychology.com/albert-ellis-abc-model-rebt-cbt/

Shuman, Vera & Scherer, Klaus. (2015). Emotions, Psychological Structure of. 10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.25007-1.

Simoni, Marcia & Dias, Murillo. (2020). LITERATURE REVIEW ON COGNITIVE BEHAVIORAL THERAPY. British Journal of Psychology. 8. 39-47. 10.6084/m9.figshare.13072643.

Yovel I. (2009). Acceptance and commitment therapy and the new generation of cognitive behavioral treatments. The Israel journal of psychiatry and related sciences, 46(4), 304–309.

Author Bios

Aliyah Arif Durrani, MA

Hello, my name is Aliyah Arif Durrani. I obtained a bachelor’s degree in psychology from Sophia College in Mumbai, and recently completed my postgraduate studies in clinical psychology at KC College in Mumbai.

I am here to serve a purpose and to deliver it in the most effective form possible. As a psychology student, my passion has served as the fuel for my advocacy efforts over the years. Such initiatives have reached communities and people with compassionate minds to better raise mental health awareness. I aim to foster emotional intelligence values in collaboration with foundations such as NutureLife and EQ4Peace to achieve individual and global peace. As a result, the paper modifies the initial contributions to such a noble cause and helps in broadening the concept of mental health beyond what it already entails.

Myron Doc Downing, PhD

Myron Doc Downing PhD has a Bachelor’s degree in Psychology, a Master’s in Social Work, and a Doctorate in Marriage and Family Counseling. He has more than 45 years’ experience as a therapist and seminar leader.

‘Doc’ Downing has six years of experience in conducting a weekly live call-in radio show, followed by a live call-in TV show. He has written several books including: TAKING CONTROL OF YOUR LIFE. He has been writing about EQ (Emotional Quotient) and how to increase your Emotional Intelligence since the 1970s.