Rarely have we seen something occur in our world that has had the impact of COVID-19. In many ways, many things have changed, and many things will never return to the way they were before. We’ve seen major changes in the way we socialize, the way we purchase goods, the way we’re entertained, and especially the way we educate our children.

For many years most children entered schools where their peers and caring adults gathered. There they would learn valuable information, but possibly more important, they would have opportunities to interact physically and socially with their peers. Historically, when kids were asked what their favorite subject is, they said recess. At the end of the day, they returned to their homes and interacted with their families. Few families attended school online. Many of those were due to being long distances from a school site. Due to COVID, that has all been turned upside down. Now most children are attending school online and only a few are attending school physically and in person.

It’s been remarkable how many educators have risen to the occasion, significantly modifying their programs and have maintained a semblance of normalcy with their students. It’s been inspiring to also see many of those educators involved in creating new strategies for classroom management, creating new curriculum methods and lessons, and new ways of helping students to bond and socialize.

As with any significant change, regardless of how good it might be, gaps are at times inadvertently created. One gap that I am concerned about is the amount of play that students of all ages are currently given or allowed.

Over the past half century, in the United States and other developed nations, children’s free play with other children has declined sharply. Over the same period, anxiety, depression, suicide, feelings of helplessness, and narcissism have increased sharply in children, adolescents, and young adults. Sociologists at the University of Michigan, who made assessments of how children spent their time in 1981 and again in 1997 found that children not only played less in 1997 than in 1981 but also appeared to have less free time for all self-selected activities. (Gray, 2011). For six- to eight-year-olds researchers found a 25 percent decrease in time spent playing, a 55 percent decrease in time spent conversing with others at home, and a 19 percent decrease in time spent watching television over this sixteen-year period. In contrast, they found an 18 percent increase in time spent in school, a 145 percent increase in time spent doing schoolwork at home, and a 168 percent increase in time spent shopping with parents. Other studies have demonstrated the reduction of such activities as free time, recess, and physical education over recent years. The cause: test preparation and coverage of standards (Gray, 2011).

What is play?

The concept of play dates back to the Greek and Roman days. But even then, and still to this day, the term is difficult to define. It’s one of those innate human conditions that an observer can see and sense it when it’s occurring but unable to find the words to describe it. In that way, it’s similar to other human conditions such as love, peace of mind, and joy.

In spite of this, experts in the field of play have developed different definitions. Dr. Stuart Brown, a Stanford professor and co-author of the book aptly entitled, Play, describes play as being innate not only to humans but also many higher-level animals. It is a contributor to survival and as important as sleep and dreaming. Brown defines play in part as being a totally volunteer activity where one loses a sense of time, a sense of self, and is without a predetermined product or purpose (Brown, 2019). True play, he describes, has the game or activity as the central purpose. If you’re playing to win, you’re probably not truly playing.

Play has gotten a bad rap over the years. Even the use of the word can create a feeling of guilt in us. In today’s society, if we aren’t being productive, learning a new skill, or making money, it’s considered a useless waste of time. We are told early in our young adulthood that anything playful or joyful can’t be good for us. It will deter us from being able to support ourselves or our family, buying that new house, or “getting ahead”. It seems that the message we get is that play puts us at risk of being last in the race, whatever race that is. “The only kind [of play] we honor is competitive play,” according to Bowen F. White, MD, a medical doctor and author of Why Normal Isn’t Healthy. It seems if an activity is fun, it can’t be productive. Similarly, in schools, if learning isn’t hard and a bit painful, it’s really not learning. It’s also considered a childhood condition that is frivolous and meaningless. To some it’s unimportant and not something adults do. Unfortunately, those thoughts can’t be further from the truth.

The Benefits of Play

Experts in the field of play are found in many different academic areas. Play has gathered attention from sociologists, psychologists, neuroscientists, medical doctors, educators, and more. Research in support of play is becoming more and more clear. Everyone agrees, though, more is necessary.

A book that initially came out in 1981, the Hurried Child, by David Elkind, describes the importance of spontaneous play. He states that during spontaneous play, children are provided the opportunity to learn about interpersonal and social relationships. Even though children do not always get along when they play, it adds on to their growing “people skills.” In today’s society, children are not allowed enough time for spontaneous play.

Jaak Paanksepp, a play researcher found that active play stimulates parts of the brain that stimulates nerve growth in the amygdala (a part of the brain that helps navigate emotions) and the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (a part where learning and decision-making is centered). His team also found a correlation between “rough and tumble” play in rats and the reduction of impulsivity in rats with frontal lobe damage. They theorize that this type of play might help people with attention deficit disorder with hyperactivity (ADHD) (1998).

Other neuroscientists have found that the amount of play influences the rate and size of the cerebellum, where attention, language processing, coordination and motor control, sensing rhythms in music, and other cognitive functions are located. Other researchers have found that play is healthy and reduces stress. They have also found its study to be more complicated than it appears. Experts in the field of play have found that play often accompanies learning and is not a distractor from it.

As evidenced, play is far from the frivolous waste of time that many of us adults think it is. Play can rarely proceed without exhibiting a positive affect and joy, the feelings of enjoyment and fun (Huizinga, 1950; Rubin, Fein, & Vandenberg, 1983). The resulting positive effects are linked to a series of cognitive benefits such as enhanced attention, improved working memory, and easier mental shifting that are all useful to learning (e.g., Cools, 2011; Dang, Donde, Madison, O’Neil, Jagust, 2012; McNamara, Tejero-Cantero, Trouche, Campo- Urriza, & Dupret, 2014). Play leads to reduced stress that is something that both children and adults need.

In addition to what neuroscientists and educators are saying, play is inherently fun. The good feelings that result from true play offer us a means to reduce the immense amount of stress and anxiety that surrounds all of us today. It has also been theorized as a possible antidote to depression and suicide.Every example of play is also evidence of learning and using social and emotional skills. It’s clear that play evolved well before the recent movement in schools towards social-emotional skill learning (SEL). It’s hard not to wonder if today’s important SEL movement exists solely to compensate for the significant reduction of play. To many psychologists, play and sports are the training ground for the future (NDF, 2015). When playing, participants constantly are required to learn how to negotiate, self-regulate, empathize with others, solve problems, cooperate, create, exercise one’s curiosity and imagination, and others SE skills. In both a child’s and adult’s world, not learning those skills may mean isolation, few friends, and challenging social situations ahead.

As you can see, the benefits of play are grand and span all aspects of our lives and growth and development, but are our students getting enough play now in these times of online learning and homeschooling?

While visiting different schools recently, I’ve been struck by how these schools are without energy, enthusiasm, and laughter. Such a tragic product of the pandemic. I couldn’t help to wonder if our students are given adequate opportunities to play, to socialize online without an agenda, to play games with peers, and to laugh out loud. I know that in some educational circles, physical education needs of children are being addressed. These are equally important and even overlap into the play arena at times. But remember that true play is without an agenda or an intended product (Brown, 2019). Published academic materials in recent years have included games for students to use to reinforce skills. But are these examples of true play? Do they include opportunities to create and imagine, to lose themselves, at to make choices, the be spontaneous and to extend the length of the activity?

Summary

With all of the benefits identified above, with play being a natural human behavior, and with play being crucial to social and emotional development, are we giving children what they need and deserve? Elkind describes what happens to children when they are pushed, gently or otherwise, into adulthood. Some results that manifest themselves in adulthood are reduced problem-solving abilities in both work and social environments, social isolation, anxiety, and depression. Play experts consider the opposite of play being depression, not work. That is because some elements of work can actually be examples of play.

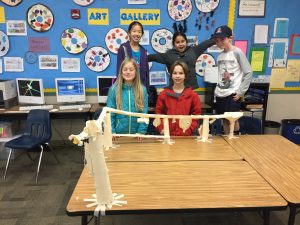

I suggest that educators and anyone who works with children of any age devote more time to giving them opportunities to play. The potential benefits, cognitive, social, and emotional, can contribute to greater, happier, and satisfied lives as both children and adults. Give time for kids to choose different activities like the creative arts, constructions of different kinds, pretending and role playing, socializing with peers, and free exploration. These are not just for young kids. They are opportunities that we all could benefit from. One just might find a more engaged and happier group of students.

Resources

- Brown, Stuart, MD, & Vaughn, Christopher; Play; Penguin Group, New York; 2019.

- Gray, Peter; Decline of Play and the Rise of Psychopathology; American Journal of Play; Spring, 2011.

- Huizinga, J. (1950). Homo Ludens, a study of the play element in culture. London: Roy Publishers.

- NDadmin; The Importance of Sports for Children; Novak, Djokovic Foundation; April 2, 2015.

- Walters, Claire; A Summary of David Elkind’s “The Hurried Child” As Told by A Future Educator, Midlothian, Virginia, January 9, 2017.

- White, Bowen, MD; Why Normal Isn’t Healthy; June 1st, 2000; Hazelden Publishing & Educational

by Dr. Bill Overton